Kathryn Kennedy, Trinity Communications

There are many recipes out there for strawberry shortcake, but Rhiannon Scharnhorst only asks her students to analyze three: One created by Betty Crocker, the second by celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse and a third by blogger Deb Perelman for her Smitten Kitchen website.

“We talk about what we see and what is the same and different in what students consider to be a pretty boring genre,” Scharnhorst explains. “Who Emeril is writing towards and who Betty Crocker is writing towards are very different — and that’s rhetoric. That’s writing knowledge, that’s contextual knowledge, historical knowledge.”

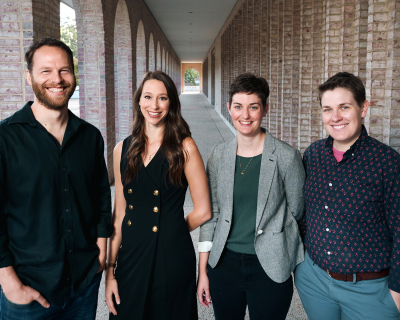

Call it writing studies, says Charlotte Asmuth. Call it “the analytic heart of writing” like Hannah Davis or “the actionable edge of the liberal arts” as David Landes does. But it’s what all four new faculty members in the Thompson Writing Program are bringing to their classrooms this fall.

“Charlotte, David, Hannah and Rhiannon are engaged teachers who create dynamic course experiences for students and place high value on peer-to-peer interaction for collaborative learning and dialogue,” says Program Director Denise Comer. “These new colleagues create inclusive classroom environments that privilege difference and encourage students to explore and share their own voices and perspectives.”

All four newcomers possess degrees in rhetoric and composition, meaning they are scholars of language differences, the ethics of oral communication, writing pedagogy and the socio-cultural histories of writing, among other areas.

But perhaps most importantly, they share a commitment to cultivating meaningful relationships with students through and with writing.

Charlotte Asmuth

Assistant Professor of the Practice

Charlotte Asmuth is enjoying learning Duke and Durham alongside the class of 2026. They love coaching young writers — as well as supporting colleagues who teach writing — and have settled in quickly, excited most by the small class sizes and opportunities for interdisciplinary interaction with faculty and graduate students on topics like program assessment and how to approach writing development with students.

“I like how writing programs can challenge misconceptions and notions about writing courses being just about literature or creative writing,” says Asmuth.

“For me, academic reading and writing practices seemed pretty mysterious,” they continue. “It wasn’t until I finished college and was starting my master’s degree that academic practices started making sense to me. But the struggles that I had as a student make me stronger as a teacher.”

One of their goals in the classroom is to “take writing off autopilot,” meaning that students begin to feel comfortable tweaking or adapting whatever they know about writing to new genres or contexts. Key to that approach is asking students to also reconsider how they read.

“Reading takes a backseat in writing classes,” Asmuth explains, “but by the time (students) get to college, they are reading much more challenging texts and they are going with strategies that they have been introduced to in middle school and coming up against a wall because they haven’t been taught to be flexible readers.”

The individualized nature of reading for all manner of texts connects to Asmuth’s research. Writing prompts are perceived differently by different people, based on lived experience. But so are many documents composed in academia and other institutions. Things that may feel mundane — an assessment rubric, a policy document — take on new meaning once they are in the hands of someone using them to achieve some end or meet a need.

“It’s a text like any other that’s open to interpretation,” Asmuth explains. “Good writing looks different depending on the context.”

David Landes

Assistant Professor of the Practice

Like reading, another under-discussed adaptive skill that can empower writers is attention – the ability to comprehend one thing in many different ways. Landes claims that attention is the secret ingredient to education: “If you’re good at attention — and specifically finding the right kind of attention — then you’re half-good at anything,” he says.

Interdisciplinary research on attention is at the core of his scholarship and informs how Landes approaches teaching. He defines attention beyond the mere ability to focus on a task or topic. Rather, he helps students recognize the many types of attention they use across their lives, which gives them more control of intellectual and aesthetic possibilities.

Communication requires “entering the world of someone else,” he explains, “and making choices from within many different worlds at once.” How does a therapist use words to help a patient heal? How does a stand-up comedian find what is funny? How do you think like an economist when talking to one, or read texts as the scholars of a particular field do?

“In navigating such worlds, what kind of tools actually help you find this thing called funny or persuasive or meaningful or therapeutic or loving or educational?” Landes asks. “These are elusive questions, and rhetoric gives us a language that is heuristic — compass-like.

“Attention can tell you what to look for or to look out for,” he says. “It helps us navigate the infinity of possible attentions and the infinity of communications that await us in future scenarios that we don't live in yet…a basis from which you make second-to-second decisions in a communicative encounter."

Landes arrived at Duke by way of Dubai, Beirut and Shanghai — international experiences that interested his students during an “ask me anything” session he held on the first day of his course titled, “Attending to Attention — The Secret Method of the Liberal Arts.” His goal is to help students find “a baseline of human honesty” that Landes says is essential for good communication and writing.

“Through casual dialogue, I’m teaching the same kind of critical lens,” he said. “I’m hearing what’s at stake in a question, what’s behind a question, what’s the audience’s motivation to a question. What do we all think when we hear this one thing? These are the attentional moves of good writers.”

He also believes time spent in the classroom should be fun for his students. He strives to create a permissive atmosphere and extends trust, embedding plenty of opportunities for “low-stakes attempts at trying new things” across a semester. He reassures students along the way that if you’re not confused, you’re not learning. “That vertigo feeling is a gift of something new entering you, not merely more information. A new idea slowbirths an unforeknowable future, and feels like it.”

As he aims for students to clarify their attentional strategies and think new kinds of thoughts, he simultaneously welcomes and encourages student diversity and style.

"Everyone comes in like a plant — different shapes, different sizes, different backgrounds,” he says. “And I'll give you sunlight, I'll give you water, I'll give you nutrients and time. And everyone will grow in different ways."

Rhiannon Scharnhorst

Lecturer

The CV section of Rhiannon Scharnhorst’s personal website declares up front in large type: “Hi there! I’m Rhiannon and, yes, I was named after the Fleetwood Mac song.” It helps people with the pronunciation, she says.

Her photo? A gleeful face behind oversized sunglasses holding two heaping scoops of ice cream on a cone — an appropriate image for a faculty member whose first Writing 101 course at Duke is titled “We Are What We Eat?”

“Food gets people into the room,” Scharnhorst says. “It’s such a good way to get people to talk about where they’re from…they talk about families, they talk about their culture, their history…we get a good sense in those conversations of how important food is to everything that we do. And that makes really good writing after the fact.”

From establishing shared interests and starting conversations, Scharnhorst will lead students through an exploration of different types of writing and the processes involved in crafting a written work. One exercise she particularly enjoys requires students to record and watch a video of themselves writing.

“Most people don’t write straightforward or linearly, but students don’t know that,” she explains. “Students think that you sit down and the muses smile upon you and it just pours out and it's perfect. And if it doesn't do that, you're a bad writer — which is so not true."

Scharnhorst’s research interests are varied, but much of her work is rooted in the mind-body connections inherent in feminist writing, particularly in how objects shape and change the embodied process of writing. She believes the objects we use to write helps us navigate how to write, as well as shaping what ultimately ends up on the page. In a recent paper, Scharnhorst highlighted how Black feminist writers in the 1980s relied on the kitchen table for writing and practicing feminism. A similarly object-based analysis is now leading her to question the role of technology in writing.

"How does (student) writing look different when they write on their phone versus a computer versus by hand?” she asks. “And not just texting, which is a different kind of valuable writing. I have students who have written whole essays on their phones. How does that change what writing actually happens on the page? What gets put down?"

A boundless curiosity and openness about her own work shapes how Scharnhorst shows up in the classroom. She plans to take students into the archives this fall and shares that her teaching is inspired, in part, by a professor she once had who “unmasked” what it meant to be a scholar.

“He would sit and think and verbalize what he was thinking to get to that answer,” she recalls. “You got to see what it looked like for an academic to think. There is not always a right or wrong answer. (As a professor) I’m thinking along with the things that I’m asking you to think about, too.

“I don’t think that there’s a division between the research that I do and the teaching that I do. I want students to see that connection happening so that they both understand the value of what I’m asking them to do as writers and that I’m also there with them, doing the same kinds of writing, just in a different space.”

Hannah Davis

Lecturer

Whether at the kitchen table or in a library carrel, writing well is hard. None of the new Thompson Writing Program faculty shy away from that notion. And Hannah Davis believes that hearing it up front helps students succeed.

“I really want students to understand that writing and language more broadly are not mysterious,” Davis says. “There’s not this magical talent that you can luck your way into or possess. These things are taught and learned as much as math and science are taught and learned.”

Her section of Writing 101 this fall — “Connecting or Connected? Human Connection in a Technologically Connected Culture” — centers on the role of technology in daily life and how it affects our ability to converse and communicate with one another. Or how we can be by ourselves. And those conversations began on day one.

“I’m impressed by Duke students’ willingness to jump in…to have conversations with each other and start to engage with ideas before they really feel ready or comfortable,” she says. “It’s great to see them wrestling with the course’s central questions and interrogating their own technology use.”

Davis’ research involves a field called “creativity studies,” which focuses on creative people, processes and products. She connects that to how writing processes can help her students, exploring concepts that are commonplace in business and engineering like design thinking or agile project management — quickly iterating, testing a product and gathering feedback.

“I do this to demonstrate the creative nature of writing and also the value of process-based writing pedagogy in helping students learn to approach writing as a dynamic, recursive exercise,” she explains.

Problem-solving practices in industry often employ brainstorming, drafting, revising and editing. So, of course, does a creative process like writing. Davis applies those principles to her own work as well.

"I enjoy the intellectual labor of academic writing,” she says. “I enjoy the wrestling that goes on when you are trying to figure out how to say what you're trying to say. The fighting with words. There's something so rewarding about it — and so productive — in taking the pieces and the parts that are there and getting it to work."

In joining the Thompson Writing Program, Davis said she has found among her colleagues “a genuine interest in teaching, in pedagogy, in engagement and working with undergrads.”

“Those pieces drew me to Duke,” she says.