Duke Today

Until recently, Huffin the Puffin -- a quirky little bird perched on a fencepost above a pebbly seashore -- existed only in Dan McShea's mind.

Then the Duke biologist tried to move his laser-sharp image of Huffin, a bedtime story character he created for his children, out of his head and onto paper.

It didn't go smoothly. Writing, it turns out, isn't easy.

So McShea joined a new initiative on campus aimed at helping faculty cultivate their writing.

This semester, McShea is one of four professors in a pilot program funded by Duke's Thompson Writing Program. It convenes once a month for members to share their writing.

And so it was that Huffin the Puffin debuted one recent morning this semester. He arrived to little fanfare; his audience was a handful of faculty members huddled around a table full of bagels and coffee. McShea read five pages aloud while others followed along on printed copies.

As writing exercises go, there isn't anything revolutionary about this approach. But unlike college students, who share and analyze each other's writings every day in composition courses, faculty -- many of whom view writing as a necessary professional evil -- rarely do, says Jennifer Ahern-Dodson, who directs the Faculty Write Program.

"The old model is to do your research and then to lock yourself away to write it up," says Ahern-Dodson, who is directing the faculty writing group. "Giving and getting feedback on writing in a collaborative way is not intuitive to a lot of faculty."

And yet, Ahern-Dodson put this pilot program together because she's heard from so many faculty members looking to advance their writing and productivity. The group is a cross-disciplinary academic amalgam. McShea is a biologist with a secondary appointment in philosophy. He's joined by two language instructors, Corinna Kahnke in German and Joan Clifford in Spanish, as well as Charlotte Clark from the Nicholas School for the Environment.

The interdisciplinary and communal nature of the group is important, Ahern-Dodson says. Most academics utilize a fairly solitary writing process: writing alone, working with one editor and then getting feedback from anonymous, external reviewers. The new model lets professors tap the wisdom of colleagues with differing expertise but similar goals, Ahern-Dodson says.

McShea was the only member to bring fiction to the group; the others each brought drafts of scholarly articles.

Joan Clifford, assistant director of Duke's Spanish language program, is writing about how language departments integrate service learning into their teaching, a topic she knows has parallels in other areas of academe.

"It's a big benefit to have an interdisciplinary group,"Clifford says. "I do think civic engagement and service learning are issues across the board."

In this group, the topics don't matter as much as the process, Ahern-Dodson said. One of the great obstacles to good writing, she adds, is carving out time each day to do it. The group's monthly meeting structure prompts members to show up once a month with five pages of new writing for discussion.

"We have competing demands for our time, especially new faculty and those who primarily teach," Ahern-Dodson says. "It's the life of an academic. So you have to prioritize writing by building it into your schedule. By committing to the writing group, writers also commit to their own writing."

By design, the group is small. There are four members this semester, and Ahern-Dodson wouldn't want more than five. The group operates behind closed doors because words, even those derived from research data, are personal. It's not easy to read your unedited work aloud. Doing so pushes the bounds of comfort.

"There's something very brave and courageous about sharing your writing," Ahern-Dodson says. "You have to establish trust and have a sense of community within the group."

McShea says he was a little nervous when he unveiled Huffin the Puffin to the group. But the protected environment, in which everyone takes a turn bearing their soul, helped.

McShea has long enjoyed writing, but soured on it a bit after so many years of science publications. He publishes journal articles regularly and has co-authored two books as well, and turned to the writing group -- and his children's story -- to recharge his batteries.

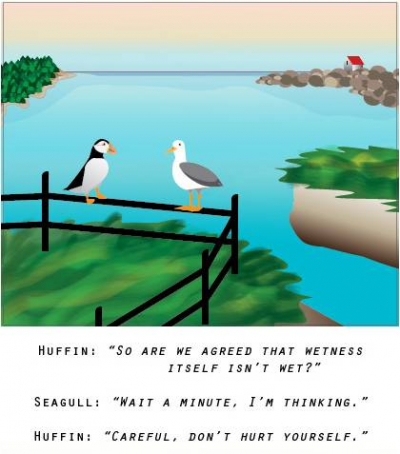

For years, Huffin has entertained McShea's two children through the conceptual and occasionally nonsensical puzzles he presents to his foil, Seagull. Huffin will ask Seagull "Is water wet?" or "Is it hotter in the city or the summer?" and Seagull will hem and haw and strain to figure out what can't be figured out.

Huffin will end each conversation by declaring: "Well, that's settled."

"It's never clear whether he really has a quandary," McShea says with a laugh. "Or whether he just wants to flummox poor seagull."

The writing group has already helped McShea find a little clarity. The group's advice has him thinking more about painting a fuller portrait of his two characters, infusing them with more detail and personality. If his fiction improves, perhaps his academic writing will as well, he reasons.

"I'm hoping that if I get into another type of writing, it rejuvenates me across the board," he says. "I want to come back fresh to my work."

The writing group meets once a month for four to six months. Faculty interested in joining a new group should contact Jennifer Ahern-Dodson at Jahern@duke.edu.